Ovid on the Vestalia

Fasti 6.249-468

Invocation (6.249-256)

Vesta, grant us your favor: now we open our lips in your service (1)

If it’s permitted for me to approach the sacred grounds (2) of your temple.

I was absorbed (3) in prayer: I felt celestial powers,

And the ground gleamed with a joyful bright light.

I didn’t actually see you, goddess — I banish the lies told by false prophets! (4)

Nor should you have been seen by a man

But the things which I hadn’t known, and by the error of which I was held,

Were made known to me without instruction.

Listen to a full recitation here!

Notes

(1) One can imagine that this portion of the Fasti might have been publicly recited during the Vestalia festival; the first two lines suggest a community gathering, as do Ovid’s rhetorical choices at the end of this selection.

(2) lit. “Your sacred things”

(3) lit. “I was entirely in prayer”

(4) lit. “Farewell to the lies of charlatan seers”

Temple of Vesta, Roman Forum

“The roofs which you see are now made of bronze, back then you would have seen thatch”

Origins of Vesta’s Cult & Temple (6.257-260)

They recall that they had celebrated the Parilia forty (5) times at Rome

When the goddess was received in the temple as the guardian of the flame

The work of the peaceful king (6) — the Sabine land bore no one more

Reverent of divine power. (7)

The roofs which you see are now made of bronze, back then you would have seen thatch,

And the wall had been woven with flexible twigs.

This little place, which supports the Atria (8) of Vesta,

Then was the great palace of bearded Numa; (9)

Meanwhile the form of the temple, as it now stands, (10)

Is said to have existed before, and a good reason for its shape lies within it.

Vesta, Earth, and Ovid’s Cosmology (6.268-282)

Vesta is in fact the same as the earth: each has (11) an untiring fire within:

The earth and the hearth (12) both indicate her seat.

The earth is like a ball (13), held up by no support,

Such a heavy weight is suspended because of air pushed under it. (14)

Its own circular motion holds up the sphere in equilibrium;

And whatever angle might press on its parts, there is none at all. (15)

And since it is placed in the middle region of things,

And it touches no side more or less,

If it weren’t round, it would be nearer to one side,

The world would not have land as its middle weight. (16)

There’s this globe (17) suspended by Syracusan art

In enclosed air, a small model of the huge heavens,

And however much the earth withdraws from the heights,

It withdraws likewise from the depths;

The round form makes it so that that can happen.

The face of [Vesta’s] temple is the same; no angle runs through it,

[And] its dome protects it from heavy rain.

(5) dena quater: “four times ten;” Ovid uses the annual Parilia festival to indicate forty years after Rome’s founding.

(6) Numa, the second mytho-historical king of Rome, supposed to have begun most of Rome’s most ancient religious customs

(7) numinis (nom. numen): a difficult word to translate; describes the inborn power of the gods; ingenium: likewise refers to innate power.

(8) Plural of atrium

(9) Intonsi: unshorn; Numa has the full beard of a Greek philosopher, a sign of respect from Ovid

(10) lit. “which now remains”

(11) subest: juxtaposed against a different use of this verb in the line above

(12) terra focusque: Latin doesn’t have the same linguistic similarity between “earth” and “hearth” as English does, but Ovid does draw a connection between them.

(13) Ovid lays out his picture of how the universe is designed as a way of explaining the connection between Vesta and the earth.

(14) aere subiecto: ablative absolute with causal sense

(15) A difficult line meaning that the sphere’s weight is distributed evenly and shaped by equal pressure from the surrounding air, resulting in no corners or angles.

(16) Ovid’s cosmology imagines a sphere with three layers: air on the outside, earth/land in the middle, and fire in the very center.

(17) Ovid describes a model he saw to explain what he’s picturing

Ovid’s Model of the Mundus

Ovid imagines a universe where the earth (both the planet and the element) exists in a sphere, rotating and keeping itself in its shape, surrounded by air. In the core of the earth, there is fire (literal fire and spiritual, elemental fire). Because fire and earth are so closely connected, this is how he connects Vesta to the earth itself.

Chastity & The Vestals (6.283-290)

You ask, “Why is the goddess attended by virgin priestesses?”

I’ll find the reasons for that also in this part [of my poem].

They recall that Ceres and Juno were born from Ops (18)

By Saturn’s (19) seed; Vesta was the third.

Each of the other two had married and were said to have born children;

Of the three there remained only one intolerant of a man.

Is it a wonder, if a virgin pleased by a virgin priestess

Accepts into her sacred rites hands that are chaste?

Vesta as Fire; Etymology (6.291-304)

Nor should you understand Vesta to be anything but living flame;

And from flame you see that no bodies are born.

Therefore she is a virgin by right, who puts out no seed

She doesn’t take [any seed], and she loves the companions of her chastity.

I foolishly (20) thought for a long time that there were images of Vesta,

[But] soon I learned that there are none beneath the curved dome [of her temple].

An eternal fire is concealed within the temple itself:

Neither Vesta nor the fire has an effigy. (21)

The earth stands by its own power: she is called “Vesta” from standing in her own power; (22)

And the reason for her Greek name could be the same. (23)

But the hearth (24) is so called from the flames and because it nourishes everything;

Which moreover was, in the old days, in the first rooms of the house.

From this also I think it is called the “vestibule;” (25)

And so when we pray we begin by saying, “Vesta, who holds the first place.” (26)

Customs of the Vestalia & Vestal Worship (6.305-318)

Long ago it was the custom to sit together on long benches in front of the hearth fires

And to believe that the gods were there at the table; (27)

Now also, when they perform the sacred rites of ancient Vacuna, (28)

The Vacunales (29) stand and sit before the hearth fires.

Something else comes into our age (30) from an ancient custom:

A pure platter (31) brings food offered to Vesta.

Look, bread hangs from donkeys, crowned,

And flowering garlands cover the rough millstones.

In earlier days farmers (32) used to bake only spelt in their ovens

And the goddess of the Ovens has (33) her own rites:

The hearth itself used to prepare bread placed under ashes, (34)

And a broken tile was laid on the warm floor. (35)

And so the baker reveres the hearth and the mistress of hearths,

And the donkey which turns the pumice millstones.

(18) = Greek Rhea

(19) = Greek Kronos

(20) lit. “I, an idiot, thought”

(21) Latin sometimes uses a double negative where we would use a singular. Literally, “Vesta nor fire has no effigy.”

(22) False etymology of Vesta from vi stando; a nod to her virginity (= independence) perhaps.

(23) Hestia from ἵστημι (hístēmi), another false etymology. Hestia’s name is the same word used for “hearth fire,” but capitalized to differentiate the goddess from the hearth: ἑστία (hestia) vs. Ἑστία (Hestia). Potest: Ovid isn’t sure.

(24) focus

(25) vestibulum, another false etymology; Ovid theorizes that the front room of the house was named because the hearth fire (= Vesta) was kept there.

(26) More likely from Greek veneration of Hestia, who was offered the first and last word/offering even when praying to other gods.

(27) The custom of lectisternium, adapted from the Greek theoxenia, where certain gods would be invited to share a friendly meal. This custom was most prominent with gods who were thought to dwell on the earth (as opposed to celestial palaces on Olympus) or to regularly visit the earth. The Dioskouroi (Castor & Pollux) in particular had this type of worship.

(28) Sabine goddess; not much is known about her

(29) Priests of Vacuna; again, not much is known

(30) lit. “into our years”

(31) patella, diminutive of patera, the usual offering dish in religious settings.

(32) A callback to Rome’s agrarian origins, typically regarded as better than “modern times.”

(33) sunt sacra deae: ethical dative, lit. “there are rites for the goddess”

(34) A traditional way of firing bread by burying it under ashes, called “ash bread” or “fire cake.” Historically in the Arab world and among Indigenous peoples of the Americas; still practiced by the Bedouin people.

(35) Presumably to cover the door to the oven.

A libation poured into a patera; Apulian red-figure volute-krater pelike; Ganymedes Painter, 4th c. BCE

The Vestals tending the hearth fire; Vierges Antiques; Jean Raoux (1727)

Millstones from Pompeii, Italy; 1st c. CE

Priapus and the Donkey (6.306-348)

Should I pass over or recount your embarrassment, red-faced Priapus?

It’s quite a funny little story. (36)

Cybele, her forehead encircled with a turreted crown, (37)

Called together the eternal gods to her celebrations;

She called the satyrs too, and the nymphs, those countryside powers.

Silenus was there too, although no one had called (38) him.

To narrate the feasts of the gods isn’t allowed (and it’s a long story):

[Suffice it to say that] the night was spent awake with lots of unmixed wine. (39)

Some wander carefree in the valleys of shady Ida,

Some lie down and raise their limbs in the soft grass;

Some are playing, sleep takes hold of others; some link arms

And strike the verdant ground three times with their foot.

Vesta lies and takes a peaceful rest in safety,

Just like that, her head supported by a bit of earth she was laying on. (40)

But the red-faced garden guardian is chasing nymphs and goddesses,

And he carries (41) his feet, wandering here and there;

And he spots Vesta: there’s doubt whether he thinks she’s a nymph

Or if he knows she’s Vesta, but he himself denies that he knew. (42)

He took up ill intentions, and he tried to approach her in secret,

And he took anxious steps, his heart beating.

By chance, Old Man Silenus had left the donkey on which he had been carried

At the sounding banks of the gentle water;

The god of the long Hellespont was about to start [on the attack],

When [the donkey] brayed with an untimely sound.

Terrified, the goddess rose with a loud cry; a whole crowd flocked together,

And [Priapus] fled through their hostile ranks. (43)

Lampsacus (44) has a custom of sacrificing this animal to Priapus,

Singing, “Fittingly we give to the flame the entrails of the informant”

Whom (45) you, goddess, decorate with necklaces of bread in commemoration;

Work stops, the empty mills become still.

(36) lit. “It’s a little story of many a joke.”

(37) frontem…redimita: lit. “encircled on her forehead,” accusative of respect. turrigera: describes the points sticking up from her crown.

(38) vocarat = vocaverat (abbreviated pluperfect)

(39) mero: The Romans considered it civilized to mix their wine with water to dilute it; unmixed wine meant barbarian excess (possibly because Cybele is a foreign goddess) and a more raucous party. nox est pervigilata: An inverse reference to Catullus V, nox est perpetua una dormienda perhaps

(40) lit. “supported with respect to her head placed on a clump of earth,” accusative of respect; fulta scans nominative and modifies Vesta in the previous line

(41) lit. “he carries and carries back”

(42) To acquit himself of the crime of attempting to assault a goddess who has declared her intent to remain chaste.

(43) Meaning, the crowd was ready to do him harm when they realized what he was up to.

(44) Lampsacos, probably the Greek nominative Λάμψακος

(45) The donkey; in memory of this myth, the donkey is sacred to Vesta and during the Vestalia donkeys are adorned with garlands made of bread

Priapus

Priapus was a fertility god, easily identified by his obvious phallus, permanently erect, in all artistic depictions. He was a god of masculinity who also protected crops (fertility of the land) and livestock. His exploits usually involved some form of attempted assault on unsuspecting goddesses or nymphs (usually thwarted as in the episode above).

The Altar of Jupiter Pistor (6.349-394)

I’ll tell you the meaning (46) of the altar of Jupiter the Baker

On the citadel of Jupiter the Thunderer - more famous for its name than its worth.

Surrounded, the Capitol was pressed by fierce Gauls:

The siege had already brought famine for some time now.

When the gods had been called to his royal throne, Jupiter

Said to Mars, “Begin.” He [Mars] stepped forward and replied:

“It’s unknown, of course, what the fortune of my people (47) might be,

And the pain of my soul lacks a voice for its complaining.

Nevertheless, if you require (48) me to report in a few words their misfortune, compounded with shame,

[In short] Rome lies under an Alpine foe.

Is this the people to whom power over everything had been promised,

Jupiter? (49) Weren’t you going to place this people over [these] lands?

They’ve already crushed the suburban peoples and battered the arms of the Etruscans:

Hope was running her course: but now she is driven out from her own hearth and home. (50)

We have seen decorated old men, triumphal, in their embroidered clothes,

Cut down in their bronzed halls; (51)

We have seen the pledges (52) of Ilian Vesta carried out from their seat:

Clearly they think that there are some gods.

But if they were to look at the citadel where you all live

And all of your homes pressed by siege,

They would come to understand, in the absence of resources, that there were no gods left,

And that incense given by an anxious hand is wasted. (53)

And if only a place for fighting lay open! (54) They would take up arms,

And, if they couldn’t win, they would fall. (55)

Now lacking resources and fearing a disgraceful fate

A barbarous horde presses them, shut in on their own hill.” (56)

Then beautiful Venus, and Quirinus with his lituus and trabea (57)

And Vesta all spoke many words in favor of Latium. (58)

Jupiter responded, “there is common concern on behalf of those walls,

And once they’re conquered, the Gauls will pay the price.

But you, Vesta, make it so that (59) they think that the food, which [in fact] is lacking, remains.

Don’t abandon your seat, Vesta!

Whatever there is of solid Ceres, (60) let an empty machine break it up

And when it’s been softened by hand, let the hearth harden it in flame.”

He had given the word, and at her brother’s orders the maiden daughter of Saturn nodded.

And now it was the middle of the night.

Already toil had given sleep to the generals. Jupiter spoke to them

And instructed them with his holy voice what he wanted: (61)

“Get up! And throw, from the top of the fortress, into the midst of your enemies,

The resource which you least want to throw.”

Sleep left them, and driven by the unusual messages, they asked themselves

Which resource it was that they would be unwilling to hand over, and which they were commanded to.

It seemed to be Ceres; (62) they threw the Cereal gifts:

They sounded, tossed onto helmets and long shields.

The expectation that they could be conquered by famine fell away: with the enemy driven back

A shining altar was set up to Jupiter the Baker.

The Lacus Curtius (6.395-416)

By chance I was returning from the Vestalia festivities on that road

The Via Nova, which now connects to the Roman forum:

There I saw a woman descend, her feet bare. (63)

I was dumbfounded and halted my pace.

An old woman (64) who was nearby sensed [what was happening], and bidding me to sit

She spoke, her head and voice trembling: (65)

“This place, where now there are fora, (66) held swamp waters;

A ditch was drenched by waters spilling out from the river.

That was the Lacus Curtius, which now supports dry altars,

Now it’s solid ground, but before, it was a lake.

The Velabra where they lead parades into the Circus,

Before was nothing but willows and hollow reeds:

Oftentimes a party guest, returning [home] near the suburban waters,

Would sing and sling drunken words at the sailors.

And that god, fitting with his many shapes,

Had not yet taken his name from the river running back in its course. (67)

Here also was a grove, thick with rushes and cane

And the swamp was not to be approached with a shod foot. (68)

The pools receded and their banks kept the waters in check,

And now the land is dry: at any rate, the custom itself remains.”

She had given her explanation. “Farewell, excellent elder!” I said,

“For what remains of your life, let everything be easy for you.”

(46) quid velit: idiomatic use of volo, velle (see L&S 4Δ)

(47) Mars was supposed to be the father of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome, and he had a vested interest in their wellbeing.

(48) exigis ut: idiomatic, “you inquire, you require an explanation”

(49) Emphatically at the start of the line. Mars is calling Jupiter out on his unfulfilled promises.

(50) Spes is imagined here as a person who made her home in Rome. Now that the city is under siege, she has taken up and left her Lares behind. The reference to household gods here should get our attention in a passage about Vesta.

(51) The war has come home.

(52) The legendary Palladium, supposedly taken out of Troy when the city had been defeated. Now (in Ovid’s day) held in the temple of Vesta. We’ll hear more about this relic below.

(53) perire: lit. “perishes”

(54) You (the other gods) don’t even have to intervene much! Just give the Romans a chance to fight - and die gloriously, if need be.

(55) As children of Mars, the Romans have virtus, the courage required to die honorably in battle rather than flee, avoid battle, or (in this case) starve to death. Mars isn’t asking for Roman victory, but for Rome’s honor to be preserved.

(56) The Palatine?

(57) lituo: (lituus) the curved staff carried by augurs, a symbol of Rome’s religiosity; trabea: mantle embroidered with red stripes, worn by government officials and a symbol of Rome’s administration.

(58) Apart from Mars, these three gods have the most interest in keeping Rome safe and secure: Venus, the mother of Aeneas (the ancestor of Romulus and Remus, and of course Augustus), Quirinus (deified Romulus, bringing with him the religious and civic symbols of Rome itself), and of course, Vesta, whose temple and eternal flame represent Rome’s lifeblood.

(59) effice: “bring it about that,” governs putentur, which in turn governs superesse.

(60) i.e. bread

(61) A different use of quid velit than above. somnum: Jupiter has come to them in a dream; the gods don’t directly appear to humans.

(62) i.e. bread; the name of the goddess stands in for what she represents or controls.

(63) Typically the gods are depicted barefoot.

(64) This epiphany of the god, a set piece found elsewhere in Greek & Roman poetry, is mediated by someone or something.

(65) The elderly are typically described as shaking.

(66) In Ovid’s day, in addition to the ancient Forum, there were the Forum of Caesar and the Forum of Augustus.

(67) averso: lit. “turning,” the god is Vertumnus, possibly Etruscan Voltumnus, whom the Romans claimed for their own after the siege of Velzna in 264 BCE.

(68) lucus: a grove, especially in Ovid, signals a locus amoenus, an untouched place in nature which signifies safety and security, and which (usually) is the site of some unfortunate event. pede velato: shoes are a sign of human invention and technology which, for the Romans, is a departure from nature. The grove allows only nature in it, so anyone looking to go there would need to be barefoot and (probably) nude. These are usually nymphs.

Mars Resting, Diego Velázquez (1638-1640)

The sale of bread at a bakery, Roman Fresco, House of the Baker, Pompeii, Italy, 1st c. CE

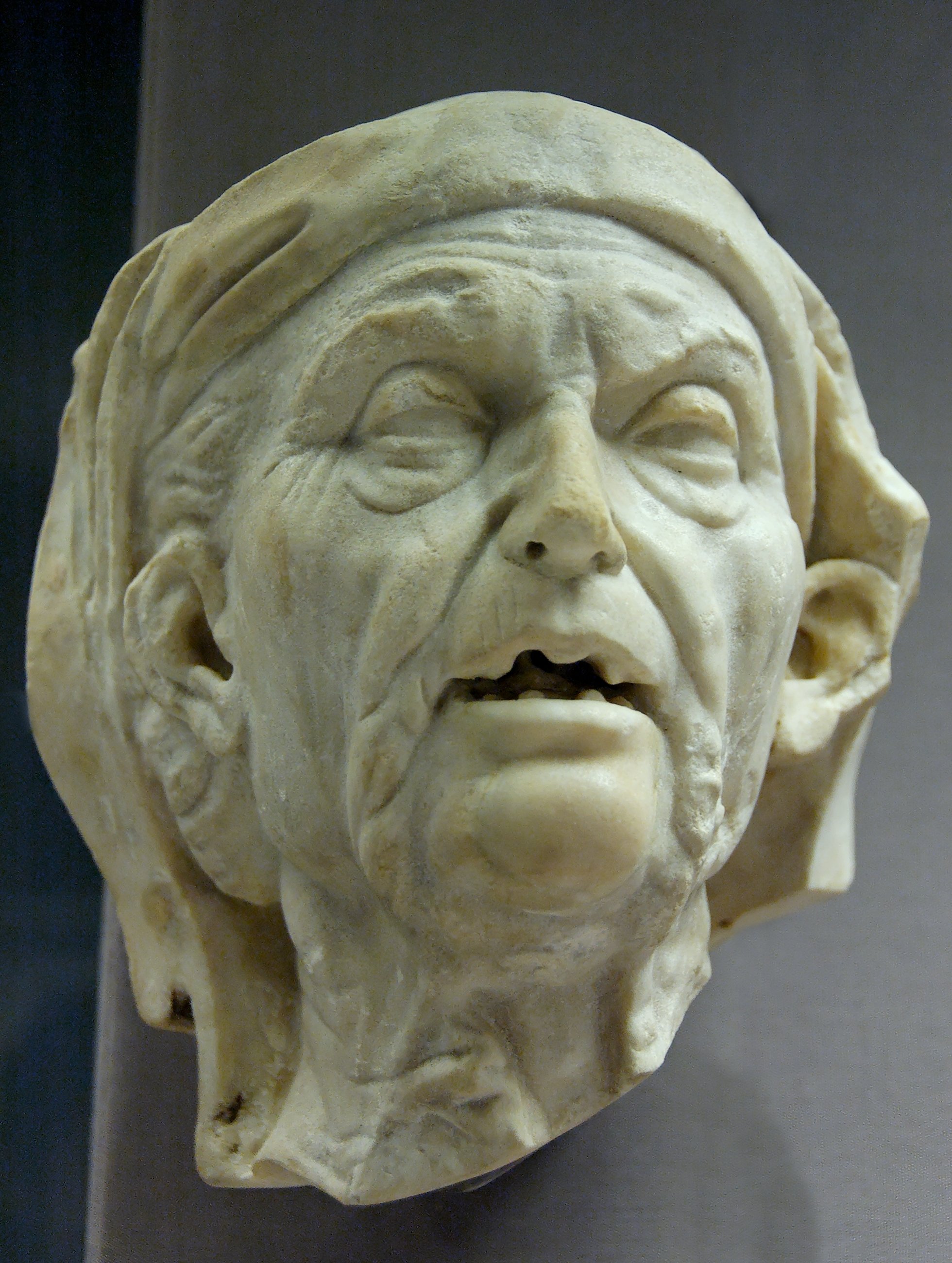

Roman head of an old woman, from a full-size statue; copy of Greek bronze (3rd-2nd c. CE)

The Palladium Comes to Rome (6.417-454)

The rest I learned long ago in my boyhood,

Nevertheless it’s for that reason that I can’t let it pass by.

Ilus, the son of Dardanus, (69) had recently made new walls

(Ilus up to that point used to have the wealth of Asia at his disposal); (70)

[When] it was believed that a celestial sign (71) of arm-bearing Minerva

Dismounted her chariot in the cities of Ilium.

I was anxious to see it: (72) I saw the temple and the place;

That’s what’s left of it: Rome holds Pallas. (73)

Smintheus was consulted, (74) and hidden (75) by the shady grove

He spoke these words with a mouth that didn’t lie:

“Protect the aetherial goddess, and you’ll protect the city:

She will transfer her power to the place.”

Ilus protected it and held it in the citadel, enclosed on the heights,

And passed down its care to his descendant, Laomedon; (76)

Under Priam it was kept safe, but not enough: this was what she wanted,

From the time when her beauty was beaten in the contest. (77)

Whether the kin of Adrastus, (78) or Ulysses, studied in the art of trickery, (79)

Or it was Aeneas, they say it was captured;

It’s unclear who did it, but the fact is, it’s Roman:

Vesta watches over it, because she sees everything with her undying light. (80)

Alas, how the Fathers (81) were afraid, at the time when Vesta

Burned and was nearly buried by her own roof!

Holy fires were blazing together with unholy fires,

And profane flames were mixed in with pious ones;

Terrified, her priestesses wept with their hair let down: (82)

Fear itself stripped away the strength of their bodies.

[When suddenly!] He came on the scene, and spoke with a great voice.

Metellus! (83) “Help! There’s no use in crying!

Take the fateful pledges [Palladium] with your chaste palms:

They aren’t for prayer, but for taking in hand.

Alas! (84) What are you waiting for?” He spoke.

He watched them hesitate and sink to their knees, trembling. (85)

He drew up some water, and lifting his hands (86) he said, “Forgive me,

These are holy: As a man, I enter [the sacred spaces] where men are forbidden to go.

If it’s a sin, (87) the punishment will come, sent to me:

Let Rome be saved by the damnation of my head.”

He spoke, and he burst in [to the temple]: when she was taken, the goddess approved of the deed,

And she was saved by the service of her priest. (88)

(69) Ilus, a mythological figure who shares his name with Ilium (= Troy); Dardanus, a mythological figure who gives the epithet “Dardanian” to the Trojans.

(70) Asia Minor (Anatolia, modern-day Turkey and its neighbors) was always associated with wealth and therefore luxury and a soft lifestyle, in both Greek and Roman literature. The wealthy aristocrats and emperors of Rome were often chastised for acting too “eastern.”

(71) The aforementioned Palladium relic, a sign of Minerva’s (Athena’s) military protection. It supposedly came to Troy in the way Ovid describes here, but the Romans ended up with it and kept it in Vesta’s temple.

(72) On his travels as a young man, Ovid likely visited the site of ancient Troy. It was typical for young aristocrats to “study abroad” as part of their education.

(73) Pallas Athena (Pallada: Greek accusative)

(74) Epithet of Apollo. As a god of prophecy, he would have been called on to figure out the meaning of this object falling from the sky.

(75) Again, the gods speak only indirectly to humans.

(76) Laomedonta: Greek accusative

(77) Minerva lost the beauty contest famously judged by Priam’s son Paris, and evidently harbored a grudge against Troy thenceforth.

(78) Diomedes

(80) Odysseus

(80) Gods associated with the sun and with fire were supposed to be omniscient, or at least be able to see things that other gods can’t. Vesta’s watchful eye and eternal flame would be effective protection for the Palladium at Rome.

(81) The senators.

(82) A traditional mourning custom.

(83) I’m playing around with these lines, trying to preserve the drama of the original. Imagine superhero music in the background.

(84) The best equivalent in modern colloquial English is probably, “Jesus Christ!” in a nonreligious sense. But, translating it that way would be confusing, for obvious reasons.

(85) lit. “and trembling, sink down with their knee having been positioned on the ground.”

(86) In prayer.

(87) i.e. “If I’m committing some kind of ritual impurity”

(88) Metellus earns the title of priest from the goddess herself for such a heroic act.

The Palladium

The Romans believed that their possession of the Palladium, which was housed in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum, symbolized the physical safety of the empire. Athena (Minerva) was supposed to have originally offered this protection to the Trojans, but when Troy fell, the Palladium was relocated, eventually ending up in Rome. The story of Aeneas (possibly the one who brought the Palladium to Italy) makes the Romans the descendants of the Trojans, and therefore the rightful owners of the Palladium and the rightful beneficiaries of the goddess’s goodwill.

Ajax drags Cassandra from the cult statue of Athena (xoanon). Roman Fresco, House of Menander, Pompeii, 1st c. CE

Our Own Times (6.455-468)

Now, holy flames, you shine under Caesar: (89)

Now the fire is and will be in Ilian hearths; (90)

And no priestess will be said to have defiled her chaplets (91)

With him as leader, (92) nor will she be buried alive in the ground:

So the unchaste perish, because, that which she has violated, into her

She is returned: Tellus and Vesta are, [after all], the same divine power.

Then Brutus (93) took the surname Callaicus for himself from the enemy

And dyed the Spanish soil with blood.

Of course, in the meantime, sadness is mixed with our joys,

Lest our festivities delight the people in their whole heart:

Crassus (94) lost his eagles and his son and his men at the Euphrates,

And in the end, last of all, he himself was given over to death.

“Parthian, what are you laughing at?” the goddess said. “You’ll give back the standards.

Someone (95) will avenge the murder of Crassus; he will be the avenger.”

(89) Caesar Augustus

(90) Both because a) Rome traces its origins back to Troy, so the Roman hearths are in a sense Ilian, and b) Asia Minor was at this point under Roman control.

(91) temerasse: abbreviated pluperfect (= temeravisse); vittas: ribbons, part of the headdress worn by both brides and Vestals.

(92) Emphatically at the beginning of the line.

(93) Decimus Junius Brutus

(94) The defeat of Crassus in Parthia was a recent and devastating loss for the Romans. Part of Augustus’ political strategy was to recover the lost battle standards (eagles), which he ultimately did.

(95) A clever way to avoid saying Augustus’ name, for the sake of Augustus’ modesty.